The war to save Africa's elephants

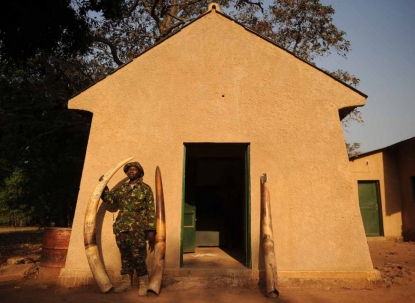

Confiscated elephant tusks. (Photo courtesy of Tristan McConnell)

Garamba National Park, DR Congo, March 16, 2016 -- We flew into Garamba National Park in a single-prop aircraft, buffeted by hot winds above a roadless, tinder dry land dotted with thatched villages. As we approached the park the flatness below became rumpled and patchily forested, hills with rocky domes burst from the ground and narrow twisting rivers sparkled through the haze thrown up by bush fires.

Photographer Tony Karumba and I visited Garamba in the northeast corner of the Democratic Republic of Congo to report on a war to protect Africa’s elephants, pitting park rangers against armed groups that profit from the sale of illegal ivory.

Win or lose?

Last year Garamba’s elephants were literally decimated, but even so the number killed was fewer than in the previous year. In the fight to save Africa’s wildlife winning and losing can look pretty similar.

During the week we spent in Garamba we watched elephants being darted and fitted with radio collars and witnessed rangers trained by former South African soldiers then deployed with them in the park’s deep north, leaping out of the helicopter because the thick bush made it impossible to set down. We interviewed rangers and the park authorities, military trainers and conservation experts to build up a picture of the scale of the challenge in Garamba.

A ranger takes up position after being deployed to a remote part of the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)

A ranger takes up position after being deployed to a remote part of the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)Gunshots were reported but no elephants were killed during our stay. The rangers told us that when the poachers come the elephants don’t stand a chance. The gunmen creep towards the elephant families armed with AK-47 assault rifles, PKM belt-fed machine guns and grenade launchers, their approach obscured by the tall grass that covers the plains. Downwind of the elephants they may as well be invisible.

From a few metres away they fire volleys of bullets. Some elephants fall at once. Others charge away in panic only to be tracked down and shot. Some escape, but many don’t. Using axes the poachers quickly chop away the tusksleaving a bloody absence where the ivory was.

A scout stands next to elephant tusks confiscated from poachers. (AFP / Tony Karumba)

A scout stands next to elephant tusks confiscated from poachers. (AFP / Tony Karumba)Populations decimated

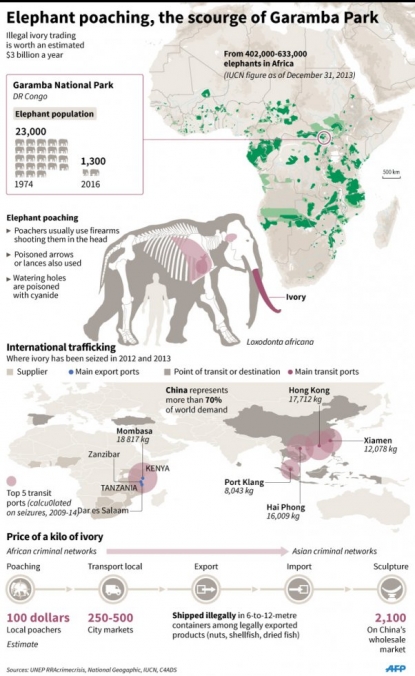

Last year 114 elephants died this way in Garamba. The year before it was 134. Back in the 1970s there were 22,000 and 500 northern white rhinos here but poaching means that today the rhinos are gone and there are perhaps 1,300 elephants left.

Across the continent – from Tanzania in the east to Mali in the west – the odds are stacked against Africa’s elephants.

Over 20,000 were killed last year for their ivory. In China, at the demand end of an illegal global supply chain controlled by international criminal gangs, raw tusks sell for over $1,100 (990 euros) a kilo.

In the strongroom at Garamba we were shown a metal trunk full of confiscated tusks, some as short as a baby’s arm, others taller than me. The heaviest of them weighed more than 32 kilos. A few metres away, across the red earth, was the old park headquarters, smashed and burned in a rebel attack seven years ago.

A ranger outpost in the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)

A ranger outpost in the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)Elephant killing is hugely profitable and Garamba’s are among the most threatened on earth, but they have allies. South Africa-based conservation organisation African Parks took over the management of Garamba a decade ago, just before poachers killed the last wild northern white rhino, and now it is fighting to stop the elephants from meeting the same fate. What they do is called conservation, but it looks more like war.

Four Garamba rangers were killed last year – we told the story of two of them, friends and comrades, who died in October – and there were twenty-eight separate firefights with poachers, among them renegade soldiers, rebel fighters, raiders on horseback and armed cattle-herders. On one occasion an unidentified helicopter flew in from the north and, after it left, eight elephants were found killed, all of them shot in the top of the skull. No one knows where that helicopter, or the three that preceded it since 2012, came from.

Elephants in the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)

Elephants in the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)The man tasked with halting the slaughter and giving the park a future is Erik Mararv whom I met at the new park headquarters on the southern bank of the tree-lined Dungu, one of the Congo River’s countless tributaries.

Erik Mararv (in cap) examines a sedated elephant. (Photo courtesy of Tristan McConnell)

The young Swede has fitted more into his 30 years than many manage in lifetime: born and brought up in the Central African Republic he dropped out of school at fifteen to train as a safari guide and hunter, spent six miserable months of 2012 in a Bangui jail – on false charges – and was once abducted by the extravagantly brutal Lord’s Resistance Army.

New threat from South Sudan

The LRA does still poach elephants in Garamba but is now a bit player, albeit one that gets undue attention thanks to its notorious violence and a frequently-applied “terrorist” label that helps fuel wrong-headed arguments that ivory poaching funds terrorism.

Mararv told me the biggest threat to Garamba’s elephants was neither LRA rebels, nor Janjaweed horsemen, nor mysterious helicopters, but gangs from South Sudan, some wearing national army uniforms. “I see the whole of South Sudan as an armed group,” he said of the war-torn nation to Garamba’s north whose violent chaos is spilling over borders in unpredictable ways. In South Sudan too, animals have fallen victim to the civil war, killed for bushmeat or for profit.

Rangers in the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)

Rangers in the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)Conservationists I spoke to credit Mararv with bringing fresh energy and courage to the fight against the poachers in Garamba. The rangers are trained hard in shooting and surviving in the bush, specially trained five-man ‘Mamba’ teams deploy for days at a time trudging through the swamps and slicing elephant grass on the lookout for poachers and their prey.

But hardware is as important as leadership and a game-changer for Garamba has been a helicopter that can transport rangers to the furthest reaches of the park. When gunshots are heard at one of the four fixed observation posts the helicopter can muster a five-man anti-poaching team within 10 to 15 minutes, quick enough, in some cases, to prevent poachers making off with the ivory or even to catch them in the act.

Rangers run toward a helicopter to be transported to a new spot within the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)

Rangers run toward a helicopter to be transported to a new spot within the park. (AFP / Tony Karumba)The helicopter allows the rangers to reach every part of the vast park, and quickly. Frank Molteno, the 60-year-old South African pilot, doesn’t mess about: when it’s time to go, he goes, banking sharply, doors open, seatbelts-be-damned.

He is a non-military man with a military manner and an aggressive impatience towards poachers. “If they see us they shoot at us, so we shoot at them,” he told me as we talked in the cockpit of his parked helicopter. “It’s bush justice.”

During October’s gun battle Molteno was nearly blown out of the sky when a poaching gang’s bullets missed severing his helicopter’s tail rotor driveshaft by half an inch. Two rangers died that day and Molteno, for all his no-nonsense bravado, tears up at the recollection yet he and the others remain unbowed.

“If I didn’t think we were going to win this, I’d quit,” he told me one evening as we stood beside the sluggish brown Dungu watching a pod of hippos yawn and splash in the rapids as the sun set over the trees.

(AFP / Tony Karumba)

(AFP / Tony Karumba)There are plenty of shortages in Garamba’s ivory war – rangers, weapons, bullets, communication and tracking equipment – but the landscape itself is an obstacle money can’t overcome.

When it rains (which it does for more than half the year) the land is inundated and the grass grows nearly three metres tall and is almost impenetrable. The few dirt roads become impassable. It can take hours to walk just a few hundred metres; visibility is close to zero: shootouts between rangers and poachers occur at extremely close range.

A scout participated in target practice. (AFP/Tony Karumba)"

But in the dry season the savannah has a monotonous, hypnotic beauty, scorched by fire, dotted with sausage trees and mostly empty of people. One day we saw a small herd of elephants close by. Hearing the car’s engine they stopped, raised their heads, then quickly turned and made for the golden light spreading across the late afternoon horizon.

The elephants have learned that people mean danger and, until that’s no longer true, knowing it might help keep them alive.

Tristan McConnell is an AFP journalist based in Nairobi. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram.

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)