Great weather for bombing

MOSCOW, October 19, 2015 -- We have an old joke in Russia saying that the most unpredictable thing about the country is its past. History can and has been rewritten in a blink of an eye. This has never been truer than with Moscow’s bombing campaign in Syria.

A civil war in Syria has been going for four years and Moscow has steadfastly supported beleaguered President Bashar al-Assad. But until a few weeks ago, Syria hadn't been the top item on the news and few Russians knew much about Moscow's Soviet-era ally in the Middle East.

And now?

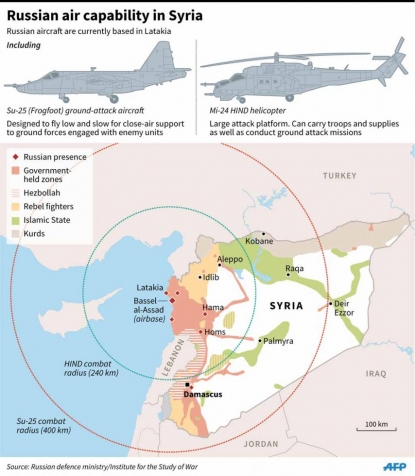

(AFP Graphics)

(AFP Graphics)And now it is “our land.” Moscow has intervened in the notoriously convoluted, multi-front conflict because the roots of Russian civilisation go all the way back to Syria, proclaimed pro-Kremlin lawmaker Semyon Bagdasarov.

"Syria is a sacred land," he said on television soon after Moscow announced the start of the bombing campaign. "For us, this is our land, our civilisation came to us from there. The first (Orthodox) monks came from Antioch," he said, referring to a city in ancient Syria. "There would be no Orthodox Christianity and there would be no Russia if it were not for Syria, if it were not for Antioch," he said.

Many Russians would certainly be forgiven for feeling confused.

After all, just over a year ago it was Crimea that was sacred, as Moscow sought to justify the annexation of the Black Sea peninsula in the face of international condemnation.

President Vladimir Putin pushed every emotional button of the collective Russian psyche.

"Here lies ancient Khersones where Prince Saint Vladimir was baptised into Christianity," he said, referring to a ruler of ancient Russia.

A man watches President Vladimir Putin's annual address to the nation in October 2006. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)

A man watches President Vladimir Putin's annual address to the nation in October 2006. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)Ever since “polite men” who Putin first denied and then later admitted were Russian soldiers, seized Crimea, Kremlin’s formidable publicity machine has been in overdrive.

A year and a half later the country is deeply polarized, with a majority supporting Putin's policies and a disapproving minority unable to make its voice heard: those who argue that Crimea rightly belongs to Russia and those who say Moscow has stolen it; those who believe Russian troops have been deployed to buttress rebels in eastern Ukraine and those who do not.

Emotions over the past months have run so high that a number of Russian media outlets switched off their comment sections to cut profanities and other unsavoury input from readers. Many people have severed ties with relatives and friends in Russia and Ukraine over the crisis.

Relatives and neighbours have stopped talking to each other because their views on the Ukraine crisis have diverged. People have “unfriended” their childhood friends on Facebook, no longer willing to hear an opposite point of view. Some Russians who were born and grew up in Ukraine now refuse to travel to the country, saying they are afraid.

Nationalist party supporters march in Kiev in October. (AFP / Anatolii Stepanov)

Nationalist party supporters march in Kiev in October. (AFP / Anatolii Stepanov)Then, after months of blanket coverage of Ukraine, the focus changed and now it’s the Syrian bombing campaign that’s dominating the airwaves. It has even made it into the weather forecast.

"Experts note the time for the start of the air operation has been chosen very well," a straight-faced female forecaster recently told viewers on the state-owned Rossiya 24 news channel. The weather in October in Syria was "ideal for carrying out operational sorties."

The images played on TV as part of the Syria coverage are worthy of a Hollywood production.

Russian jets take off into the night sky. Russian reporters are rushed into Moscow's Syria airbase and newspapers plaster pictures of the soldiers wearing sand-coloured uniforms at the newly-built camp, complete with its own canteen and a makeshift Russian banya for the boys.

A Russian pilot at Russia's Syria base. (AFP Photo / Komsomolskaya Pravda / Alexander Kots)

A Russian pilot at Russia's Syria base. (AFP Photo / Komsomolskaya Pravda / Alexander Kots)"For the first time in the 21st century Russia established a military base in a region which has traditionally been considered a sphere of influence of other countries," proudly proclaimed Komsomolskaya Pravda, one of the country's most popular dailies.

Even the defence ministry's unwieldy PR machine has sprung to life, briefing reporters daily, posting results of the Syrian raids on its Facebook page and releasing slickly produced videos of cruise missile strikes.

Russian fighter jet takes off in Syria. (AFP Photo / Komsomolskaya Pravda / Alexander Kots)

Russian fighter jet takes off in Syria. (AFP Photo / Komsomolskaya Pravda / Alexander Kots)The authorities have even flown the Red Star Army Chorus and Dance Ensemble to the Hmeimim airbase in Latakia to help keep up the spirits of the military, said the defence ministry's official newspaper.

It noted that the troupe was continuing the tradition of singers who went to battle zones during World War II and the Afghanistan conflict to entertain Soviet troops.

There are no reports of casualties and Putin has denied claims of those as "information warfare."

Soldiers check a Russian fighter jet before takeoff in Syria. (AFP Photo / Komsomolskaya Pravda / Alexander Kots)

Soldiers check a Russian fighter jet before takeoff in Syria. (AFP Photo / Komsomolskaya Pravda / Alexander Kots)The campaign has had an effect. Last month, 69 percent of Russians were against Moscow's deployment of troops in Syria. Today more than 70 percent approve of Moscow's bombing campaign, according to a poll from the respected Levada Centre.

"They thought it was bad, then they watched television and decided it was good," Maxim Trudolyubov, the opinion page editor of the liberal business newspaper Vedomosti, wrote on Facebook.

A Russian flag with Vladimir Putin's image flies above his supporters during a Moscow rally in 2012. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)

A Russian flag with Vladimir Putin's image flies above his supporters during a Moscow rally in 2012. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)Of course, not everyone has bought the official line. After the "our land" comments, social networks exploded with derision.

Get ready Africa and Latin America, wits joked. "Next in line will be Peru with its petroglyphs," quipped one commentator. "They will decipher Putin's name and send bombers there."

The humour is bittersweet. Russia's Syrian bombing campaign has become the latest reminder to the ever-dwindling liberal minority in Russia that it seems to be forced to relive the lives of their parents in their own mad version of Groundhog Day.

A photo from 1991 shows a woman next to removed Soviet symbols in Moscow. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)

A photo from 1991 shows a woman next to removed Soviet symbols in Moscow. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)As young adults, their parents lived through the slow, suffocating decay of the Soviet Union in the late 1970s and early 1980s, under Leonid Brezhnev and his successors Yury Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko.

Lack of political reforms, a planned economy, falling oil prices, the Cold War, US sanctions, a massive

militarisation of society, foreign policy blunders, the occupation of Afghanistan and blanket state propaganda marked those days. The stagnation era.

Then came perestroika, the fall of Communism, nascent democracy, and by the time they entered adulthood in a new, modern, market-oriented Russia, they wondered how their parents could have lived like that.

Today they’re finding out.

Vladimir Putin is presented as Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in a caricature. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)

Vladimir Putin is presented as Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev in a caricature. (AFP / Alexander Nemenov)In his 15 years years in power, Putin neutered the opposition, placed television under state control and alienated the West, before the annexation of Crimea last year sank relations to post Cold War lows. Critics say that today’s Kremlin’s PR machine outdoes even that of its Soviet predecessors.

Pro-Kremlin youth activists march under a poster reading "Go Putin's Generation!"(AFP/Alexander Nemenov)

Moscow's foray into the war-torn Middle Eastern country has also raised the ghosts of the past, stirring memories of the Kremlin's disastrous venture into Afghanistan in 1979. The risk of getting mired in a new distant war is not lost on the Kremlin and the general public, even if there are little public comparisons between the two conflicts.

The Kremlin's original plan for a six-month intervention in Afghanistan went awry, with the war eventually claiming more than 14,000 Soviet troops over a decade and the government maintaining a veil of secrecy over the drawn-out operation.

Russian troops pull out of Afghanistan in May 1988. (AFP / Vitaly Armand)

Russian troops pull out of Afghanistan in May 1988. (AFP / Vitaly Armand)The authorities maintain that the bombing campaign in Syria is nothing like Afghanistan and never will be. The Kremlin has ruled out boots on the ground and said that even if someone ends up taking part in ground operations, he would do so voluntarily.

Russians are hoping their leaders will get it right this time.

"There won't be a second Afghanistan," said my landlady, who like millions of others has applauded

Putin for presiding over Moscow's assertive foreign policies after the country’s perceived humiliations of the 1990s.

"Putin is smarter than Brezhnev. He is an intellectual."

Anna Smolchenko is an AFP reporter based in Moscow. Follow her on Twitter @Annaafp

(AFP / Ria Novosti / stringer)

(AFP / Ria Novosti / stringer)